VESSEL: Seeing Double

Noa Weiss and Nora Raine Thompson, The Brooklyn Rail

Noa Weiss and Nora Raine Thompson, The Brooklyn Rail

Two writers wade into the hazy environment of David Thomson’s new work to grapple with opacity and transparency, the magical and mundane. Where one sees an M, the other sees a W, yet both come away with a sense of intimacy in the unknown.

Sharing Opacity —Nora Raine Thompson

We are instructed to take off our shoes and sequester our phones in labeled envelopes, then stand in a make-shift room of black curtains to breathe, intentionally. This is all before entering the space of David Thomson’s newest work, VESSEL. But what we enter is another interstice. The audience is scattered on the felt-clad floor of The Chocolate Factory, surrounding what seems to be the “vessel” itself—a partitioned area encased by white swaths of fabric. This inner sanctum’s walls bend into an M shape, whose transparency is constantly, almost imperceptibly, changing as the light shifts. Throughout the evening, six performers, Thomson included, dance, wail, touch, and rest inside (and, briefly, outside) the cloth walls.

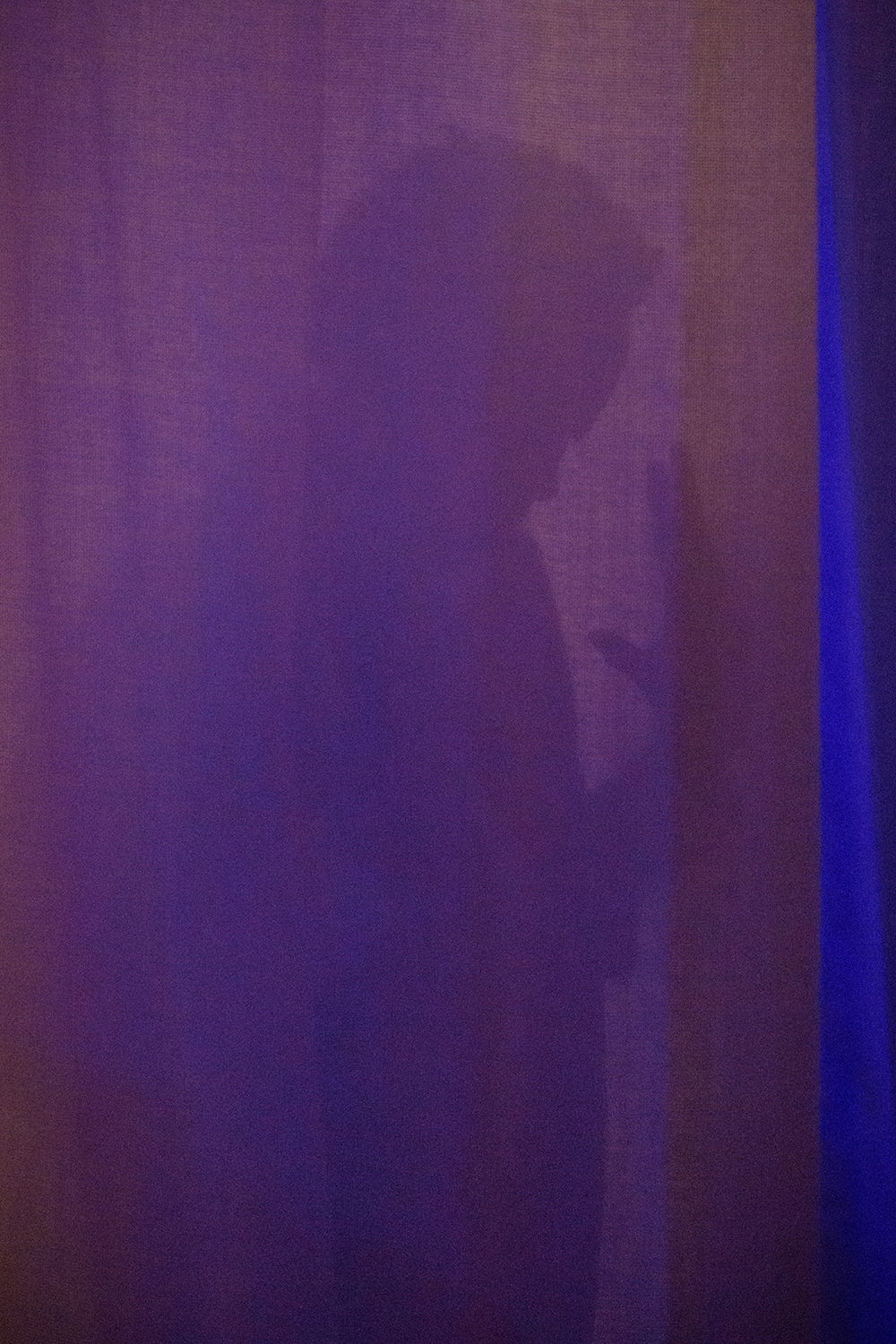

When I arrive, Thomson is outside the vessel, moving among the audience in a black floor-length apron, hands clasped over his front, composed. He later slips into the folds of the cloth, his darkly cloaked outer persona seeming to dissolve into an inner one, donned in white and silver, like the others. On the inside, he moves with blurry yet precise abandon, cheered on by a chorus of sighs and hums. Although the performers’ visual edges are hazy, their voices carry as if over water. It is potent, their singing. At one point, like a lullaby, it makes my jaw slacken.

For a long time, it seems, all the performers stay inside, building a world rife with interaction and relation, its own culture, its own characters. One performer, shrouded in a blanket, approaches the walls often, a sliver of their face exposed, though nearly impossible to make out. They emit soft mouthy clicking sounds, like the echolocation of a bat. I can only hear them when their body is less than a foot away from mine, which gives me a glimpse of clarity and closeness, even while muffled visually by the veil between us. Opacity, Thomson shows us, does not preclude intimacy.

I had been excited to experience VESSEL’s version of “opacity,” a term coined by Caribbean theorist Édouard Glissant in 1990 that Thomson explicitly cites as an influence. In Glissant’s essay in Poetics of Relation entitled, “For Opacity,” he theorizes “transparency” as the phenomenon of “‘understanding’ people and ideas from the perspective of Western thought” through measurement, and thus a reduction. An assumption of “transparency” posits that everything and everyone is know-able, that difference can be visualized, explained, and/or flattened. In contrast, a “right to opacity” allows for the presence of unknown and unseen depths, not only of another, but even of oneself. Thomson has been toying with ideas of ambiguity and blurriness within his own body for years, as observed by Tara Aisha Willis in her 2016 article, “Stumbling into Place,” in which she describes the contradictions of Thomson’s moving body, including its “visibility and obscurity.”

I am not surprised, then, that this work features a literal, material manifestation of this “right to opacity” —the walls that keep most of the movement concealed within the vessel. But I am surprised to see someone other than Thomson emerge from the vessel later in the evening. Donning a drab coat over their shining dress, the performer holds their hands close to their body just like Thomson did when he was on the outside. They trace the cloth walls, walking slowly, as if ensuring the boundaries are stable. The action inside the vessel is growing into a chaotic revelry, maybe enabled by the presence of this composed representative, holding the edges. Maybe this is a protective move, an offering of visibility to stave off prying eyes who demand transparency.

As a dance writer, for years I have been steeped in questions of how to witness ethically. I attempt to describe dances without dissecting them, without claiming I can know all of what they are made of. As a white person deeply imbricated in what Glissant might call “Western thought,” these questions have also been ever-present in reckoning with my socialization to always try to understand, explain, or see into.

In considering these impulses and efforts, I find myself entranced not only by the movement beyond and around the veil, but also by the veil itself. How might entitlement to a certain kind of knowing be disrupted, here, by this gauzy white cloth and its protectors?

The fabric’s weave crisscrosses itself, intricate, absorbing light and color and shadow capriciously. I can see the texture of what separates us, I can imagine its roughness on my skin. I can sense the many threads, enmeshed, that make up this in-between. There is complexity in this cloth meant to obscure, mirroring the questions I sense are swirling for Thomson in VESSEL, and for me, in responding. How do you share something without reducing it? How do we connect without merging?

I feel the end coming when the fabric, slowly and suddenly, becomes totally opaque, sheet white. Sound diminishes while staff gently inform the audience that “the space is coming to a close.” I hang around for a bit in the lobby after the performance. Aptly, not long enough to see the performers emerge in street clothes, but just long enough to hear a spill of relieved laughter from inside the vessel.

Playing with the Unseen and Everyday — Noa Weiss

For three hours, VESSEL wavered between magical and mundane. Days after experiencing the installation, it is still difficult to determine which side it falls on. Judging from the program notes, that ambivalence seems to be the intended takeaway.

In a sense, the installation was comprised of known factors: a long loop of light cues, metallic costumes, a swath of white fabric, mouth sounds, a group of experienced improvisers doing high level, but straightforward, improv. What made the piece exquisite was that the audience matched the performers in their commitment to duration and discovery. VESSEL ended up being a collective score, a way for the viewers to improvise through the installation and emerge with new discoveries.

It starts when you walk into The Chocolate Factory. After leaving your shoes and phone in the lobby, you enter an intermediary curtained space, which connects to the main viewing area. Filled with scattered seats and cushions, the performance space contains one main focal point: a towering white curtain that juts out in a W-shape, containing the cast of performers.

The enclosure brings up multiple conflicting images: a zoo, a sanctuary, a cloister, a glimpse into another dimension. As the performers build momentum, their energy swells into ecstatic movement and resounding harmonies. During these moments, being a viewer feels like sitting outside a house party — the evidence of a lively gathering leaks out around you, just out of reach. At other points, observing the listless movements of the people behind the curtain feels sinister, voyeuristic.

Are they on display, or protected? Can they feel us watching?

The barrier also allows for unexpected moments of intimacy. After sitting off to the side, I move closer to the curtain, a few feet away from one of the performers. We are separated only by the fabric, and as they dance, I feel the reverberations of their steps rise through my body. They move, unguarded, and I watch with an equal lack of restraint.

Over the course of a few hours, I see multiple audience members whip their heads around as the overhead speakers emit sound. James Lo DJ’s a set of vocalizations similar to the ones coming from behind the curtain, but louder, more intimate. Tongue clicks and gasps echo around the room, trailing down the necks and over the shoulders of the audience.

I spend most of the time waiting for one grand climax, but leave with a series of small stunning fragments. After a prolonged period of straining to make out movement behind the curtain, I feel the house lights dim. The lighting change reveals a figure standing in a ghostly green glow, shifting back and forth and fluttering their fingertips in the air. The sudden detail of it shocks me. Later, up near the curtain, a performer pounds out a rhythm on the floor. A responding sound comes from an unseen place further back. The beats sync, converse, and dissipate — a correspondence between the visible and invisible.

Most memorable is a moment of unexpected tenderness. One performer curls up on their knees in child’s pose, arms outstretched. Another performer strokes their back, running their hands along the sides of their partner’s spine. The feeling is immediately familiar, and I feel ambushed by the combination of relatability and distance. As I sit against the wall with my friend’s head in my lap, I’m struck by how similar and how separate our experiences are.

The October 26, 2022 iteration of VESSEL was full of lush, sensational dancing and brilliantly improvised vocal harmonies. Yet in the wash of obscurity and waiting, what remains of VESSEL are the private surprises, orchestrated through Thomson’s commitment to extended, intentional observation.